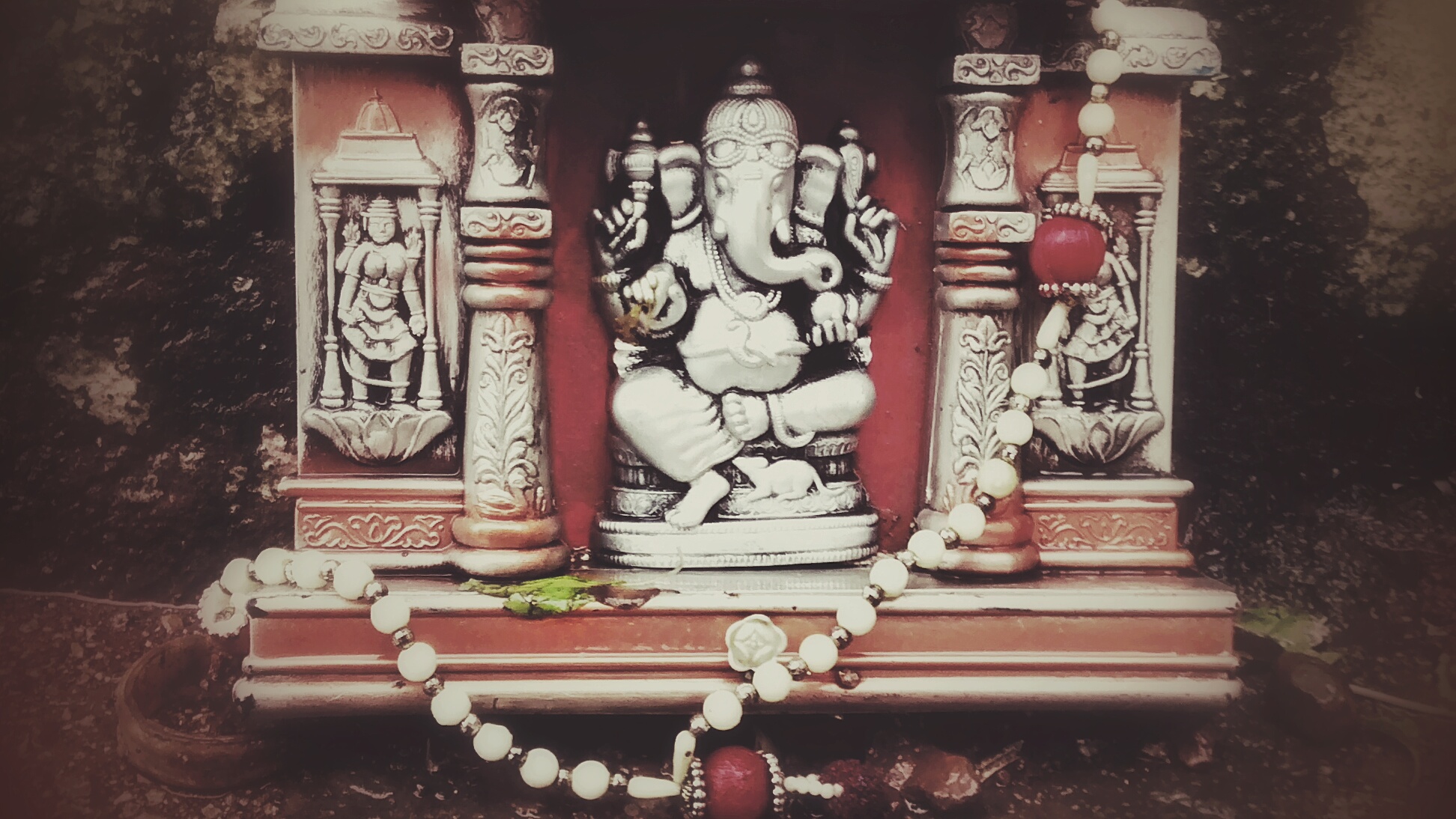

“O.K., so tell me,” I continued. “Going to a temple, standing before the idol of a deity and looking – or gazing – at it because either (a) one has been forced to do so by one’s elders, (b) everybody else is doing it, (c) it would be impolite or disrespectful to not do so, or, (d) it’s the done thing… Do any of these things constitute Darshan?”

“Of course not,” she shot back. “That’s mere mechanical form! There’s no reverence behind it, no devotion, there’s no…”

She paused thoughtfully. And then her eyes went wide as saucers as her palm slapped her forehead. “Oh My God, I get it!!!”

I just smiled. “Go ahead, say it. There’s no what?”

“There’s no Feeling. No Connection,” she said, her eyes still wide in wonder. “No connection between perceiver and the object of perception!”

She’d got it. Well, almost all of it. All that was left for me to do was fill in the blanks and connect the dots.

“Drishti,” I said, then paused for effect. “What exactly does it mean? Your name. What does it mean, Drishti?”

“Vision,” she said, a confused look on her face. To be wiped off a moment later with a look of comprehension.

“Nope,” went I. Vision is something far deeper. The wordDrishti actually means “Sight”, to look at. It is a function of the eyes. It is something we all do. The ‘photographer’ who takes a picture without knowing why he’s taking it has Dhristi, as does a person who merely looks at the idol in the temple – or gazes at it without feeling and connection. All this is Drishti. Drishti is mere looking, Drishti is mere sight. Nothing more.”

“And Darshan?” she ventured.

“Tell me, when you’ve gazed at the idol in a temple with real feeling, have you at times experienced the idol gazing back?”

“Yes, many a times,” she said.

“And it was only when the intensity of your feeling towards the idol was… well, quite intense, isn’t it?”

“Absolutely,” she said, a bit confused about what I was pointing to.

I rested my elbows on my knees, leaning forward. “Remember what I often say with respect to photography: that if you really, really observe something for long enough, it’ll literally tell you how to go about photographing it. Have you tried – and experienced – this for yourself?”

I wish that I had a camera to photograph her eyebrows. They shot so high they almost went off her scalp.

“Oh yes I do! My God, I can’t believe the similarities,” she exclaimed.

“They’re not similar, they’re the same thing! That something that you observe which tells you how to photograph it — it really cannot tell you how to go about photographing it. Nor can the idol gaze back at you. Not literally. Not unless there is something more at work, and that more has nothing to do with mere Sight – nothing to do with Drishti. But rather, it has everything to do with you – with your feeling. That feeling – and there is nothing exclusive to religion about it – is what in India is called “Bhaav” or Emotion. It is this Bhaav that cements the connection – the link – between the object of perception and the perceiver. It is this connection – and this alone – that is responsible for the child being able to make an emotive drawing of a family outing. It is this connection – and this alone – that makes an inanimate object speak to you on how it should be photographed. It is this connection – and this alone – that makes the idol gaze back. It is this connection – and this alone – that all art, all photography, all music is all about at the end of the day!”

I paused, my response having emptied my lungs of air. She was silent, soaking in what I’d said. A few seconds passed before I continued.

“That connection,” I went on, “is all that matters. And that connection is entirely within you being the perceiver. Being within you, it is distinct from Sight (Drishti). It is – and I cannot emphasize this enough – it is beyond mere looking, beyond mere sight. It is literally In-sight! A feeling, no matter how fleeting or transitory, of the relationship – the connection – between you and your… call it whatever you wish to, they’re all the same at the end of the day: object of affection, devotion, observation, perception, what you wish to photograph… It’s the same thread running through everything. Do you understand what I’m saying, Drishti?”

She chose not to answer my question. She just smiled and went “The camera really doesn’t matter, The Connection does. That’s Darshan!”

I smiled back, knowing that the time for words was over. Drishti had had her Darshan.

(Strange as it may sound, to be continued)